Remote viewing represents one of the most fascinating intersections of consciousness studies, quantum physics, and human potential. This natural ability—sometimes described as a form of “mental Wi-Fi”—allows individuals to perceive and describe distant locations, objects, or events without using their conventional senses. Far from being supernatural or paranormal, remote viewing is increasingly understood as an expression of our innate psi functioning, a natural human capacity that exists on a bell curve like any other ability.

The scientific exploration of remote viewing has progressed from classified government programs to peer-reviewed academic research, revealing compelling evidence that challenges our conventional understanding of consciousness and perception. This guide explores the scientific principles, historical development, and practical applications of remote viewing, providing both theoretical understanding and hands-on techniques for developing your own remote viewing abilities.

Scientific Principles Behind Remote Viewing

Remote viewing challenges our conventional understanding of perception and consciousness. While skeptics may dismiss it as impossible, several scientific frameworks offer potential explanations for how remote viewing might function. These theories draw from quantum physics, consciousness studies, and information theory to explain how the human mind might access information beyond the constraints of time and space.

Quantum Mechanics and Non-Local Consciousness

Quantum mechanics provides perhaps the most compelling scientific framework for understanding remote viewing. Several quantum phenomena appear particularly relevant:

Quantum Entanglement

When two particles become entangled, they form a single quantum system regardless of the distance separating them. A change to one particle instantaneously affects its partner, a phenomenon Einstein famously called “spooky action at a distance.” As physicist Anton Zeilinger explains in his book Dance of the Photons, “Entanglement describes the phenomenon that two particles may be so intimately connected to each other that the measurement of one instantly changes the quantum state of the other, no matter how far away it may be.”

This non-local connection might provide a model for how consciousness could access information at a distance. If consciousness operates at a quantum level, it might similarly transcend spatial limitations through entanglement-like processes.

The Observer Effect

In quantum physics, the act of observation affects the behavior of subatomic particles. This suggests a fundamental relationship between consciousness and physical reality. Physicist Dean Radin proposes that this relationship might extend beyond the microscopic level, allowing consciousness to interact with distant systems through intentional observation.

Remote viewing could represent a specialized application of this observer effect, where trained practitioners direct their attention to specific targets and receive information through this quantum-consciousness interface. The consistent results across multiple studies suggest this is not merely coincidental but reflects a genuine capacity of human consciousness.

Non-Local Consciousness Theories

Several theoretical frameworks attempt to explain how consciousness might access information beyond conventional sensory channels:

David Bohm’s Implicate Order

Physicist David Bohm proposed that reality consists of an “explicate order” (the physical world we perceive) and an “implicate order” (a deeper level where everything is interconnected). According to this model, consciousness may access the implicate order, retrieving information that appears non-local from our conventional perspective.

Remote viewing might represent a process of “unfolding” information from the implicate order into conscious awareness. This would explain why remote viewing seems to transcend spatial and temporal boundaries—in the implicate order, such distinctions may be less rigid than in our everyday experience.

Biocentrism and Consciousness-Centric Models

Robert Lanza’s theory of biocentrism suggests that consciousness is fundamental to reality, not merely an emergent property of physical processes. In this framework, space and time are constructs of conscious perception rather than absolute realities.

If consciousness is indeed primary, it might naturally possess capabilities that transcend physical limitations. Remote viewing could represent an expression of consciousness operating according to its fundamental nature rather than the constraints we typically impose on it through our materialist assumptions.

Electromagnetic Field Hypotheses

Some researchers have proposed that remote viewing might involve interactions with electromagnetic fields:

Global Consciousness Project Findings

The Global Consciousness Project, led by researchers at Princeton University, has documented correlations between global events and patterns in random number generators. These findings suggest that consciousness may interact with physical systems in ways that transcend conventional understanding.

Similar mechanisms might underlie remote viewing, with consciousness interacting with electromagnetic fields to access information about distant targets. This could explain why geomagnetic activity appears to correlate with remote viewing performance in some studies.

Geomagnetic Correlations

Research by James Spottiswoode has identified correlations between remote viewing success and geomagnetic activity. His analysis of 2,879 free-response trials showed that remote viewing accuracy was significantly higher during periods of low geomagnetic activity, with effect sizes approximately 380% stronger than during active periods.

This suggests that electromagnetic fields may play a role in remote viewing, either facilitating or interfering with the process depending on their state. Such correlations provide an important avenue for understanding the physical mechanisms that might be involved.

Information Transfer Models

Several models attempt to explain how information might be transferred in remote viewing:

Signal Non-Locality

Physicist Harold Puthoff, who directed the CIA’s remote viewing program at Stanford Research Institute, proposed that remote viewing might involve a form of “signal non-locality” distinct from quantum non-locality. In this model, information transfer occurs through channels that don’t require the transmission of energy or signals through conventional space-time.

This framework aligns with observations that remote viewing accuracy doesn’t diminish with distance and isn’t blocked by electromagnetic shielding—characteristics that would be expected if conventional signals were involved.

Puthoff’s Virtual Reality Metaphor

Puthoff has also suggested a virtual reality metaphor for understanding remote viewing. Just as users in a virtual reality environment can access any location in the virtual world regardless of their avatar’s position, consciousness might similarly access information throughout physical reality from a more fundamental level of existence.

This model helps explain why remote viewing often provides accurate conceptual information while sometimes missing specific details—the process may involve translating information from a more fundamental level into the viewer’s conscious awareness, with some loss of fidelity in the process.

Deepen Your Understanding of Remote Viewing Science

Want to explore the scientific principles behind remote viewing in greater depth? Our comprehensive research collection includes summaries of key studies, theoretical papers, and experimental protocols.

Historical Development of Remote Viewing

The systematic study of remote viewing emerged during the Cold War, when intelligence agencies sought unconventional methods for gathering information. What began as a classified government program eventually developed into a rigorous scientific discipline with standardized protocols and methodologies.

The Cold War Origins: Government Programs

Project SCANATE and Early CIA Involvement

Remote viewing research began in earnest in 1972 when the CIA funded a program at Stanford Research Institute (SRI) led by physicists Harold Puthoff and Russell Targ. Initially codenamed Project SCANATE (for “scan by coordinate”), the program aimed to determine whether individuals could accurately describe distant locations identified only by geographic coordinates.

The program’s early success with talented viewers like Ingo Swann and Pat Price led to increased funding and expanded research. In one notable early experiment, Swann accurately described a Soviet facility at Semipalatinsk, including details of a large gantry crane that were later verified through satellite imagery.

The Stargate Project

By 1977, the Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA) had taken over funding for remote viewing research under the umbrella of what would eventually become known as the Stargate Project. This program continued for over two decades, employing a cadre of remote viewers to gather intelligence on targets of interest to various government agencies.

During its operation, the program reportedly provided valuable intelligence on a wide range of targets, from the location of kidnapped individuals to details of foreign military installations. According to declassified documents, remote viewers successfully located a downed Soviet bomber in Africa, described the health of American hostages in Iran, and provided information about weapons factories in Siberia.

Declassification and Public Awareness

The 1995 CIA Declassification

In 1995, the CIA declassified much of the government’s remote viewing program, acknowledging its existence and releasing thousands of pages of documents detailing experiments and operational applications. This declassification came as part of a broader review ordered by President Clinton through Executive Order Nr. 1995-4-17, which emphasized “commitment to open Government.”

The released documents revealed that the program had continued for over two decades with funding of approximately $20 million, involving multiple intelligence agencies and producing results that were deemed significant enough to warrant this sustained investment.

The AIR Evaluation

Following declassification, the American Institutes for Research (AIR) conducted an evaluation of the remote viewing program. The evaluation, led by statistician Jessica Utts and skeptic Ray Hyman, produced mixed conclusions. Utts determined that the statistical evidence for remote viewing was robust and replicable, writing that “the statistical results of the studies examined are far beyond what is expected by chance.”

Hyman, while acknowledging the statistical significance of the results, questioned whether they constituted sufficient evidence for the reality of remote viewing. This tension between statistical significance and theoretical explanation continues to characterize scientific debate about remote viewing.

Standardization of Protocols

Development of Controlled Remote Viewing (CRV)

As research progressed, Ingo Swann and military intelligence officer Skip Atwater developed a standardized methodology called Controlled Remote Viewing (CRV). This six-stage protocol was designed to provide a structured approach to remote viewing that could be taught and replicated.

CRV broke the remote viewing process into distinct stages, from initial impressions to detailed analytical information, allowing for a systematic approach to gathering and evaluating information. This methodology became the standard training protocol for military remote viewers and continues to influence remote viewing practice today.

Academic Research Protocols

In parallel with government programs, academic researchers developed their own protocols for studying remote viewing. These included the ganzfeld procedure, which uses sensory deprivation to facilitate psi functioning, and various forced-choice and free-response methodologies designed to provide quantifiable results.

These academic protocols emphasized experimental controls and statistical analysis, addressing criticisms about methodology and providing a foundation for peer-reviewed research. They have been crucial in establishing remote viewing as a legitimate subject for scientific inquiry.

International Research Efforts

While the United States conducted the most well-documented government remote viewing program, evidence suggests that other countries pursued similar research:

Soviet and Russian Programs

The Soviet Union reportedly invested significantly in psychic research through programs at the Institute of Radio Engineering and Electronics. According to declassified CIA documents, the Soviet program included research on remote viewing, psychokinesis, and other psi phenomena.

After the fall of the Soviet Union, some research continued under the Russian Academy of Sciences. Former Soviet researchers like Larissa Vilenskaya later collaborated with Western scientists, providing insights into the Soviet approach to psi research.

Chinese Research

China has conducted extensive research into what they term “exceptional human body functions” since the 1980s. This research, centered at institutions like the Chinese Academy of Sciences, has included studies of remote viewing abilities in children and adults.

Chinese researchers have published numerous papers on their findings, though language barriers and different research traditions have limited integration with Western research. Nevertheless, their work represents an important parallel tradition in the scientific study of remote viewing.

Discover the Classified History of Remote Viewing

Fascinated by the government’s secret remote viewing programs? Our historical timeline provides a comprehensive overview of declassified projects, key personnel, and remarkable operational successes.

Scientific Evidence for Remote Viewing

The scientific evidence for remote viewing comes from multiple sources, including government-sponsored research, academic studies, and meta-analyses that aggregate results across multiple experiments. This body of evidence provides a compelling case for the reality of remote viewing as a genuine human capability.

Key Studies and Their Findings

Stanford Research Institute Studies

The SRI studies, conducted by Puthoff and Targ from 1972 to 1995, represent some of the most rigorous research into remote viewing. Their findings, published in respected journals including Nature and the Proceedings of the IEEE, demonstrated statistically significant results across multiple experimental designs.

In one series of experiments, viewers were asked to describe distant locations being visited by a “beacon” person. The accuracy of these descriptions, as evaluated by independent judges, far exceeded chance expectations. Particularly impressive were “outbound” experiments where viewers successfully described locations that would be randomly selected only after they had recorded their impressions.

Princeton Engineering Anomalies Research (PEAR)

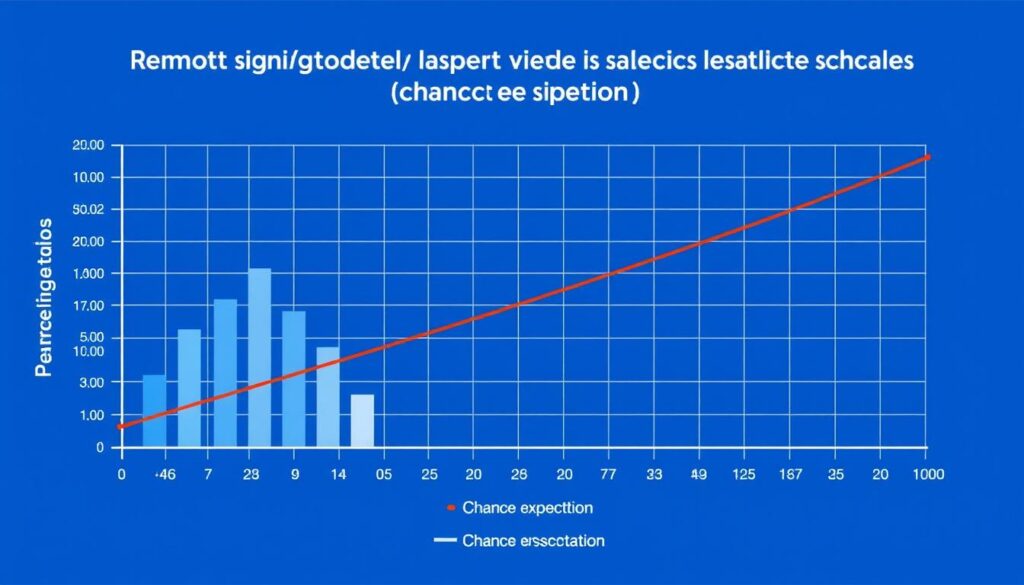

The PEAR laboratory at Princeton University, led by Robert Jahn and Brenda Dunne, conducted remote viewing experiments from 1979 to 2007. Their research involved 411 formal remote viewing trials with 227 participants, demonstrating statistical significance exceeding odds of a billion to one against chance.

Particularly notable was their finding that remote viewing accuracy appeared independent of distance and time—viewers could describe locations thousands of miles away with the same accuracy as nearby locations, and could describe future locations (precognitive remote viewing) as accurately as present ones.

Ganzfeld Studies

The ganzfeld procedure, which uses mild sensory deprivation to facilitate psi functioning, has produced some of the most consistent evidence for remote viewing capabilities. In these experiments, a “receiver” in the ganzfeld state attempts to describe a target being viewed by a distant “sender.”

A meta-analysis of 79 ganzfeld studies comprising hundreds of individual trials, conducted by psychologists Daryl Bem and Charles Honorton, found a combined statistical significance of almost one in a billion against chance. These results have been replicated across multiple laboratories and research teams.

Precognitive Remote Viewing

Studies of precognitive remote viewing—where viewers describe targets that will be randomly selected in the future—provide particularly compelling evidence. Since the targets don’t exist at the time of viewing, these studies effectively rule out conventional explanations like sensory leakage or electromagnetic signals.

Physicist Russell Targ and his colleagues at SRI demonstrated successful precognitive remote viewing in multiple studies, including a series where viewers accurately predicted changes in silver commodity futures, resulting in substantial financial gains that were reported in the Wall Street Journal.

Meta-Analyses and Replications

Utts Meta-Analysis

Statistician Jessica Utts conducted a comprehensive meta-analysis of government-sponsored remote viewing research as part of the 1995 AIR evaluation. Her analysis found that the statistical evidence for remote viewing was “far beyond what is expected by chance” and comparable to the evidence for accepted phenomena in other fields.

Utts concluded that “the statistical results of the studies examined are far beyond what is expected by chance” and that “arguments that these results could be due to methodological flaws in the experiments are soundly refuted.” This analysis remains one of the most authoritative evaluations of the remote viewing evidence base.

Bem’s Feeling the Future

Psychologist Daryl Bem’s “Feeling the Future” experiments, published in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, demonstrated precognitive effects across nine experiments involving over 1,000 participants. While not specifically focused on remote viewing, these studies provide important evidence for retrocausal phenomena that align with precognitive remote viewing findings.

Bem’s meta-analysis of these experiments showed a statistical significance of more than six standard deviations from chance expectation, representing odds of more than a billion to one against chance. These findings have been independently replicated by other researchers.

Expert Assessments

“The statistical results of the studies examined are far beyond what is expected by chance. Arguments that these results could be due to methodological flaws in the experiments are soundly refuted.”

“I started out as a skeptic, but the overwhelming evidence from the SRI experiments convinced me that something was going on. The results were just too consistent and the quality of the remote viewing descriptions too impressive to dismiss.”

Criticisms and Responses

Methodological Criticisms

Critics like Ray Hyman have raised concerns about methodological issues in remote viewing research, including potential sensory leakage, experimenter effects, and data selection biases. These criticisms have led to improvements in experimental protocols, including double-blind designs, pre-registered analyses, and independent judging procedures.

Modern remote viewing experiments typically employ rigorous controls that address these concerns, including automated target selection, separation of experimenters and participants, and standardized evaluation procedures. These methodological improvements have not diminished the statistical significance of the results.

Theoretical Objections

Some critics argue that remote viewing contradicts established scientific principles and therefore cannot be valid regardless of the empirical evidence. This position, sometimes called the “impossibility argument,” reflects a philosophical rather than scientific approach to evaluating evidence.

Proponents respond that science progresses precisely by discovering phenomena that challenge existing theories, and that quantum mechanics already provides theoretical frameworks that could potentially accommodate remote viewing. They argue that empirical evidence should guide theory development rather than being dismissed based on theoretical preconceptions.

Key Scientific Papers on Remote Viewing

- Puthoff, H. E., & Targ, R. (1976). A perceptual channel for information transfer over kilometer distances: Historical perspective and recent research. Proceedings of the IEEE, 64(3), 329-354.

- Jahn, R. G. (1982). The persistent paradox of psychic phenomena: An engineering perspective. Proceedings of the IEEE, 70(2), 136-170.

- Bem, D. J., & Honorton, C. (1994). Does psi exist? Replicable evidence for an anomalous process of information transfer. Psychological Bulletin, 115(1), 4-18.

- May, E. C., Spottiswoode, S. J. P., & James, C. L. (1994). Shannon entropy as an intrinsic target property: Toward a theory of psi. Journal of Parapsychology, 58, 384-401.

- Utts, J. (1996). An assessment of the evidence for psychic functioning. Journal of Scientific Exploration, 10(1), 3-30.

Access the Scientific Evidence

Want to examine the scientific evidence for yourself? Our curated collection includes summaries of key studies, statistical analyses, and expert commentaries on the most compelling research.

Practical Remote Viewing Techniques

Remote viewing is not just a subject for scientific study—it’s a practical skill that can be learned and developed with proper training and practice. The following techniques are based on protocols developed during government programs and refined through decades of experience by professional remote viewers.

Preparing for Remote Viewing

Creating the Optimal Environment

Remote viewing is best practiced in a quiet, comfortable environment with minimal distractions. Choose a location where you won’t be interrupted and where ambient noise is minimal. Some viewers prefer dim lighting, while others work well in normal light—experiment to find what works best for you.

Temperature is also important—if you’re too hot or too cold, physical discomfort can distract from the subtle impressions of remote viewing. Wear comfortable clothing and ensure good air circulation in your viewing space.

Mental Preparation

Before beginning a remote viewing session, take time to quiet your mind and achieve a relaxed but alert state. Many viewers use a brief meditation or breathing exercise to clear mental chatter and enhance receptivity to subtle impressions.

The ideal state for remote viewing combines relaxation with focused attention—too much relaxation can lead to drowsiness, while too much focus can create analytical overlay that interferes with direct perception. With practice, you’ll learn to recognize and maintain this balanced state.

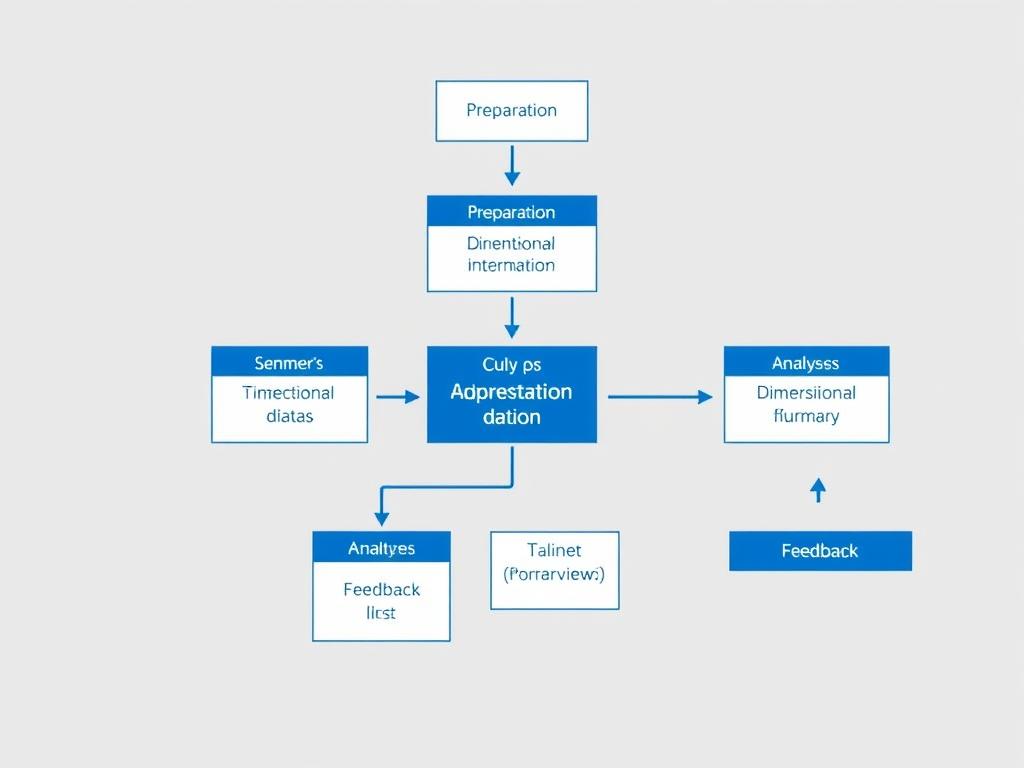

Basic Remote Viewing Protocol

The following seven-step protocol is adapted from Controlled Remote Viewing (CRV) methodology developed for government programs. It provides a structured approach suitable for beginners while incorporating elements used by experienced viewers:

- Preparation: Sit comfortably at a table with blank paper and a pen. Take several deep breaths and clear your mind. State your intention to perceive the target accurately.

- Target Assignment: Work with a partner who selects a target (or use a pre-selected target in a sealed envelope). The target should be identified only by a random number or coordinate—you should have no prior knowledge of what it represents.

- Initial Impressions: Allow your mind to become receptive to initial impressions—these might include colors, shapes, textures, temperatures, or emotional feelings. Write or sketch these impressions without analyzing them.

- Sensory Data: Expand your awareness to include more detailed sensory impressions—sounds, smells, tastes, and tactile sensations associated with the target. Record these without trying to identify what they represent.

- Dimensional Information: Begin to perceive spatial relationships, dimensions, and movement associated with the target. Sketch these aspects, focusing on relationships rather than identifications.

- Analytical Overlay: At this stage, your mind will naturally begin to form conclusions about what the target might be. Record these thoughts but recognize them as analytical overlay rather than direct perception.

- Summary and Feedback: Review your notes and sketches, then create a summary of your impressions. Only after completing this summary should you receive feedback about the actual target.

Advanced Techniques

Coordinate Remote Viewing

Coordinate Remote Viewing uses geographical coordinates (latitude and longitude) as the target identifier. This technique, developed by Ingo Swann, allows for precise targeting of specific locations without providing any sensory cues to the viewer.

To practice this technique, have a partner select a location and provide only its coordinates. Focus your attention on these coordinates as you follow the basic remote viewing protocol. With practice, you may find that the numerical coordinates serve as an effective “address” for your consciousness to locate the target.

Associational Remote Viewing (ARV)

Associational Remote Viewing is a specialized technique used for predicting future outcomes with binary or multiple choices. In this approach, distinct targets (usually images) are associated with potential outcomes, and the viewer attempts to describe which target they will be shown in the future.

This technique has been used successfully for predicting stock market movements and other future events. It leverages the apparent ability of remote viewing to transcend time as well as space, accessing information about future feedback sessions.

Extended Remote Viewing (ERV)

Extended Remote Viewing uses a deeper state of relaxation, similar to light trance, to enhance receptivity to target information. In this approach, the viewer typically reclines rather than sitting at a desk, and may work with a monitor who records their verbal descriptions.

ERV sessions often last longer than standard CRV sessions and may produce more detailed and immersive perceptions. However, they also require greater skill in distinguishing between genuine perceptions and imagination or dreams.

Blind Target Exercises

Blind target exercises provide structured practice with immediate feedback. In these exercises, a series of distinct objects are placed in opaque envelopes or containers, and the viewer attempts to describe the contents of a randomly selected container.

This approach allows for rapid skill development through immediate feedback and multiple practice trials. It’s particularly useful for developing confidence in distinguishing between genuine impressions and analytical overlay.

Common Challenges and Solutions

Analytical Overlay

Analytical overlay—the tendency to analyze, interpret, or name impressions prematurely—is perhaps the most common challenge in remote viewing. This mental noise can obscure genuine perceptions and lead to inaccurate results.

Solution: Practice separating direct perceptions from interpretations. Record raw impressions (colors, shapes, textures) before attempting to identify what they represent. With practice, you’ll learn to recognize and set aside analytical processes during the perception phase.

Mental Noise

Mental noise includes distracting thoughts, worries, expectations, and desires that interfere with clear perception. This noise can be particularly problematic when viewing emotionally charged targets or when under pressure to perform.

Solution: Regular meditation practice can help reduce mental noise. During viewing sessions, acknowledge distracting thoughts without engaging with them, then gently return your attention to the target. The structured protocol helps maintain focus despite occasional mental noise.

Displacement

Displacement occurs when a viewer accurately perceives a target other than the intended one. This might be a different target in the same series or something entirely unrelated but significant to the viewer.

Solution: Maintain clear intention to perceive the specific target identified by the assigned coordinate or number. Some viewers find that writing the target identifier at the top of each page helps maintain focus on the correct target.

Feedback Dependency

Some viewers become overly dependent on immediate feedback, which can limit their ability to work with targets where feedback is delayed or incomplete. This dependency can also reinforce patterns of perception that may not be optimal.

Solution: Practice with a mix of targets—some with immediate feedback, others with delayed feedback. Focus on the process rather than results, trusting that accurate perceptions will emerge with consistent practice regardless of feedback timing.

Remote Viewing Strengths

- Accessible to most people with proper training

- Provides verifiable results through blind protocols

- Can access information regardless of distance

- Not blocked by physical barriers or shielding

- Can provide unique perspectives on problems

- Develops with practice like any other skill

Remote Viewing Limitations

- Rarely 100% accurate or complete

- Subject to analytical overlay and mental noise

- Results can be difficult to interpret

- Performance varies between sessions

- Emotional targets can be challenging

- Requires patience and consistent practice

Master Remote Viewing with Our Step-by-Step Guide

Ready to develop your remote viewing skills? Our comprehensive guide includes detailed protocols, practice targets with feedback, and troubleshooting advice for common challenges.

Applications of Remote Viewing

Remote viewing has been applied in various contexts beyond scientific research and intelligence gathering. As understanding of this ability grows, so too does the range of its practical applications.

Historical Applications

Intelligence Gathering

The most well-documented application of remote viewing has been in intelligence gathering. During the Stargate Project, remote viewers provided information on Soviet weapons facilities, located downed aircraft, and assisted in hostage situations.

According to declassified documents, remote viewing was used to locate a Soviet Tu-95 bomber that had crashed in Africa, to monitor Chinese nuclear tests, and to gather intelligence on various facilities that were inaccessible through conventional means.

Archaeological Applications

Remote viewing has been used to locate archaeological sites and provide information about ancient civilizations. In one notable example, archaeologist Stephan Schwartz used remote viewers to locate the lighthouse of Pharos and the tomb of Cleopatra in Alexandria, Egypt.

These archaeological applications demonstrate how remote viewing can provide practical information that can be verified through subsequent physical investigation, offering a unique complement to conventional archaeological methods.

Contemporary Applications

Missing Persons Cases

Remote viewing has been applied in missing persons cases, with viewers attempting to describe the location or condition of missing individuals. While results in this area are mixed, there have been documented cases where remote viewers provided accurate information that assisted in locating missing persons.

Organizations like the Applied Precognition Project and the International Remote Viewing Association occasionally work with law enforcement on missing persons cases, typically on a pro bono basis and following strict ethical guidelines.

Business Applications

Some businesses have explored remote viewing for market research, product development, and strategic planning. Associational Remote Viewing (ARV) has been particularly useful for predicting market movements and making investment decisions.

In one documented case, a team led by Russell Targ used ARV to predict silver commodity futures, generating significant profits that were reported in the Wall Street Journal. Similar approaches have been applied to other financial markets and business forecasting scenarios.

Medical Applications

Remote viewing has been explored as a complement to conventional medical diagnosis, with viewers attempting to describe internal conditions that might not be apparent through standard examinations. This application remains experimental but has shown promising results in some cases.

Research by Larry Dossey, M.D. and others has explored the potential of remote perception in medical contexts, suggesting that it might provide valuable insights when used alongside conventional diagnostic techniques.

Personal Development

Many individuals practice remote viewing for personal development rather than practical applications. The discipline required for successful remote viewing—quieting the mind, distinguishing between direct perception and interpretation, maintaining focused awareness—can enhance overall cognitive functioning and self-awareness.

Remote viewing training often leads to improved attention, enhanced creativity, and greater intuitive awareness in everyday life, making it valuable even for those who don’t apply it to specific practical problems.

Ethical Considerations

Privacy Concerns

Remote viewing raises important questions about privacy, as it potentially allows access to information that would otherwise be private. Responsible practitioners emphasize the importance of ethical guidelines and respect for personal boundaries.

Most remote viewing training programs include ethical codes that prohibit viewing targets without appropriate permission, particularly when those targets involve private individuals or sensitive personal information.

Verification and Accuracy

Remote viewing is rarely 100% accurate, which raises ethical concerns about its application in high-stakes contexts. Responsible use requires acknowledging the limitations of the technique and using it as one source of information among many rather than as a definitive guide.

In practical applications, remote viewing data should be verified through conventional means whenever possible, and decisions should not be based solely on remote viewing information without corroborating evidence.

Remote Viewing Ethics Guidelines

- Respect privacy and obtain appropriate permissions for viewing targets involving individuals.

- Acknowledge the limitations of remote viewing and avoid making definitive claims based on unverified perceptions.

- Use remote viewing as a complement to, not a replacement for, conventional information gathering methods.

- Be transparent about the nature and limitations of remote viewing when sharing results with others.

- Avoid using remote viewing for personal gain at others’ expense or for purposes that could cause harm.

Frequently Asked Questions About Remote Viewing

Is remote viewing real or just pseudoscience?

Remote viewing has been studied under rigorous scientific conditions for decades, with results published in peer-reviewed journals including Nature and the Proceedings of the IEEE. Statistical analyses of these studies show effects far beyond chance expectation, with odds against random occurrence exceeding one in a billion in some meta-analyses.

While the underlying mechanisms remain unclear, the empirical evidence for remote viewing is robust and has been replicated across multiple laboratories and research teams. The phenomenon challenges conventional scientific models but is supported by substantial empirical evidence that meets standard scientific criteria for establishing the reality of a phenomenon.

Can anyone learn remote viewing, or is it only for naturally gifted psychics?

Research indicates that remote viewing ability exists on a bell curve like any other human trait—some people have natural aptitude, most have moderate ability that can be developed with training, and some may struggle to develop the skill. Studies at both SRI and PEAR found that ordinary individuals with no prior psychic experiences could be trained to perform successful remote viewing.

Professional remote viewing trainer Paul H. Smith, who worked with the military’s Stargate Project, estimates that about 1% of the population has exceptional natural ability, about 80% can develop useful skill with proper training, and about 19% may have difficulty developing the ability despite training. The key factors appear to be proper instruction, consistent practice, and the ability to quiet analytical thinking.

Is remote viewing dangerous?

Remote viewing, when practiced according to standard protocols, has not been associated with negative psychological or physical effects. The thousands of sessions conducted during government programs and subsequent civilian training have not produced evidence of harm to properly trained viewers.

However, like any mental discipline, remote viewing should be approached responsibly. Viewers should maintain psychological boundaries, avoid becoming obsessed with the practice, and seek proper training rather than experimenting haphazardly. Those with pre-existing mental health conditions should consult with healthcare providers before engaging in any practice that involves altered states of consciousness.

Can remote viewing predict lottery numbers or be used for gambling?

While remote viewing has shown statistical success in predicting binary outcomes (such as up/down market movements), it has not proven reliable for predicting specific numbers like lottery results. The complexity and randomness of such targets, combined with the psychological pressure of potential financial gain, typically interferes with accurate perception.

Associational Remote Viewing (ARV) has been used successfully for predicting market movements, but even these applications show mixed results and require careful protocol design to minimize psychological biases. Remote viewing is best applied to targets with clear feedback mechanisms and minimal emotional investment from the viewer.

How does remote viewing differ from other psychic abilities like clairvoyance?

Remote viewing differs from traditional concepts of psychic abilities primarily in its structured methodology and empirical approach. While clairvoyance refers generally to gaining information beyond conventional senses, remote viewing specifically involves a standardized protocol designed to minimize bias and produce verifiable results.

Remote viewing was developed as a trainable skill rather than a mysterious gift, with emphasis on documenting impressions, separating perception from interpretation, and evaluating results against objective feedback. This structured approach distinguishes remote viewing from more general concepts of psychic functioning and makes it more amenable to scientific study and practical application.

Conclusion: The Future of Remote Viewing Research

The science behind remote viewing continues to evolve, challenging our understanding of consciousness and perception while offering practical applications across various fields. As research methodologies improve and theoretical frameworks develop, remote viewing is gradually moving from the fringes of science toward greater acceptance in mainstream scientific discourse.

The evidence accumulated over five decades of research strongly suggests that remote viewing represents a genuine human capability—one that transcends conventional understanding of space and time but can be studied using standard scientific methods. While the underlying mechanisms remain unclear, the empirical evidence for the phenomenon is robust and compelling.

For those interested in exploring remote viewing personally, the structured protocols developed through government programs and subsequent civilian research provide a practical pathway to developing this natural human ability. With proper training, consistent practice, and an open but discerning mind, most people can experience some degree of success with remote viewing.

As physicist Harold Puthoff concluded after decades of research, “The integrated results appear to provide unequivocal evidence of a human capacity to access events remote in space and time, however falteringly, by some cognitive process not yet understood.” This capacity represents not just a scientific curiosity but a profound opportunity to expand our understanding of human consciousness and its relationship to the physical world.

Begin Your Remote Viewing Journey Today

Ready to explore your own remote viewing abilities? Our comprehensive starter kit includes everything you need to begin practicing this fascinating skill—from basic protocols to practice targets with feedback.